# Operators

Operators are elemental programming building block which are found at the heart of every C++ statement. Operators are a symbolic representation of a single, simple task that needs to be performed by the computer. Most are based on familiar concepts and are therefore easily understood. Others are associated with more complex concepts and are therefore covered in future chapters.

Key Insight - Operator

Operators are a symbolic representation of a single, simple task that needs to be performed by the computer.

Operators perform their action on or with operands, be it expressions or values.

Key Insight - Expression and Statement

An expression is "a sequence of operators and operands that specifies a computation" (that's the definition given in the C++ standard). Examples are x, x + 5, and round(12.44). Even an assignment x = 5 is an expression in C++. That's why the following is valid in C++: x = y = b + 3

The rule is that an expression must result into a single value.

A statement is a chunk of code that performs an action and is terminated by a semicolon ;.

So basically x = y + 3; is a statement that consists of the three expressions y, y + 3 and x = y + 3.

# Arithmetic Operators

The most basic operators are the Arithmetic operators. They are easy to understand because they have the same functionality as in math. The following operators are available to do basic math operations:

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

+ | Additive operator (also used for String concatenation) |

- | Subtraction operator |

* | Multiplication operator |

/ | Division operator |

% | Remainder operator |

These operators are part of the binary operators because they take two operands, namely a left and a right operator. For example in the summation below left is the left operand and right is the right operand. The result of the operation is stored in the variable sum.

int right = 14; int left = 12; int result = left + rights; // Result is now 26Copied!

2

3

4

The +, - and * operators function the same as in math. Their use is demonstrated in the next code snippet.

int a = 2 + 3; // a = 5 int b = a + 5; // b = 10 int c = 6 * b; // c = 60 int d = c - 120; // d = -60Copied!

2

3

4

5

The division and remainder operators deserve some special attention. The division operator has a different result based on the types of its left and right operand. If both are of an integral type (short, int, byte) then a whole division will be performed. Meaning that 3 / 2 will result in 1. If either operand is a floating point operand (float or double) than the division operator will perform a real division: 3.0 / 2 will result in 1.5.

If your operands are of integral type and you wish to perform a real division, you can always multiply one of the operands with 1.0 to explicitly convert it to a floating point number without having to change its actual data type. Study the examples in the following code snippet.

int x = 5; int y = 2; int z = x / y; // z = 2 (whole division) double w = x / y; // w = 2.0 (still whole division) double q = 1.0 * x / y; // w = 2.5 (real division) double a = 3.0; double b = 2; // 2 will actually be converted to 2.0 double k = a / b; // k = 1.5 (real division)Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Notice that even double w = x / y; results in 2.0. The reason behind this is that x / y equals to 2 as it is a whole division since both operand are of integral type. The result is then implicitly converted to a double, and stored in w.

While the precedence (order) in which mathematical operations are performed is defined in C++, most programmers do not know all of them by heart. It is much more clear and simpler to use parentheses () to enforce the precedence of the calculations. Take a look at the following piece of code:

int a = 5; int b = 6; int c = 10; int d = 2; int result = a * b + c - d * a / 5 - 3; // result = 35 std::cout << "The result is " << result << std::endl;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

The result of the code above is 35. Would you have known? By using parentheses this becomes much clearer and the chance of making a mistake is a lot smaller.

int a = 5; int b = 6; int c = 10; int d = 2; int result = (a * b) + c - (d * a / 5) - 3; // result = 35 std::cout << "The result is " << result << std::endl;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Operators that have the same precedence are bound to their arguments in the direction of their associativity. For example, the expression a = b = c is parsed as a = (b = c) because of right-to-left associativity of the assignment. The expression a + b - c is parsed (a + b) - c because of left-to-right associativity of addition and subtraction.

# Increment and Decrement Operators

Incrementing (+1) and decrementing (-1) a variable is done very often in a programming language. It is one of the most used operations on integral values. It is most common used in loop-constructs as will become clear in the next chapters.

Because of this a shorter way has been introduced using an increment ++ or decrement -- operator as shown in the following code example.

int i = 5; i++; // Same as writing i = i + 1; i--; // Same as writing i = i - 1;Copied!

2

3

4

There is however a caveat to keep in mind. Both operators come in a suffix (e.g. i++) and a prefix (e.g. ++i) version. The end result of both versions is exactly the same, but there is a difference if their value is assigned to another variable or when it is used inside another expression.

Take a look at the following two examples. The first example focusses on the prefix version. In this case the value of i will be incremented to 6 before its value will be assigned to the variable b. Meaning at the end of this code both i and b will have a value of 6.

int i = 5; int b = ++i; // b = 6, i = 6Copied!

2

The next example demonstrates the suffix version. In this case the value of i will first be assigned to b before it is incremented. This results in b having a value of 5 and i having a value of 6 at the end of the example.

int i = 5; int b = i++; // b = 5, i = 6Copied!

2

While this may not seem all that important at the moment, it will be when arrays and loop-constructs are introduced.

# Comparison Operators

Comparison (aka relational) operators are used to compare two values with each other.

The table below shows the available comparison operators that can be used in C++ to build conditional expressions.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

== | equal to |

!= | not equal to |

> | greater than |

>= | greater than or equal to |

< | less than |

<= | less than or equal to |

Since a conditional expression actually produces a single true or false result, this result can actually be assigned to a variable of type bool.

Take a look at some examples of comparison operators:

int a = 4; int b = 8; bool result; result = (a < b); // true result = (a > b); // false result = (a <= 4); // a smaller or equal to 4 - true result = (b >= 9); // b bigger or equal to 9 - false result = (a == b); // a equal to b - false result = (a != b); // a is not equal to b - trueCopied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Note how two equality signs == are required to test if two values are equal, while a single assignment sign = is used to assign a value to a variable.

While the comparison operators will not often be used in a situation as shown in the previous code, they will often be used to make decisions in code.

# Logical Operators

More complex conditional expressions can be created by combining multiple conditional expressions. This can be achieved by using the logical operators.

The table below gives an overview of the available logical operators in C++.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

&& | AND |

|| | OR |

! | NOT |

These work as you know them from the Boolean algebra. The || (OR) operator will return true if either of the operands evaluate to true. The && (AND) operator will return true if both operands evaluate to true. A logical expression can be negated by placing the ! (NOT) operator in front of it.

The code example below checks if a person is a child, an adult or an adolescent based on his/her age.

int age = 16; bool isAChild = (age >= 0 && age <= 14); // false bool isAnAdolescent = (age > 14 && age < 18); // true bool isAnAdult = (age >= 18 && age <= 75); // falseCopied!

2

3

4

# Lazy Evaluation

The logical operators exhibit "short-circuiting" behavior, which means that the second operand is evaluated only if needed. This is also called lazy evaluation. So for example in an OR statement, if the first operand evaluates to true the outcome must also be true. For this reason the second operand is not checked anymore.

This can lead to confusing C++ constructions which should be avoided when possible. However as a future professional C++ programmer you may encounter them and need to understand their behavior.

An example where the second operand of the condition is not checked:

int counter = 0; bool result = (false && counter++); std::cout << "Counter: " << counter << std::endl; std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;Copied!

2

3

4

Output

Counter: 0 Result: 0

And an example where the second operand of the condition is always evaluated:

int counter = 0; bool result = (true && counter++); std::cout << "Counter: " << counter << std::endl; std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;Copied!

2

3

4

Output

Counter: 1 Result: 0

Do note that in the last example the postfix operator is used and not the prefix operator. Meaning that the value of counter is evaluated before it is incremented. As its initial value was 0 it is evaluated to false, meaning that result is assigned false.

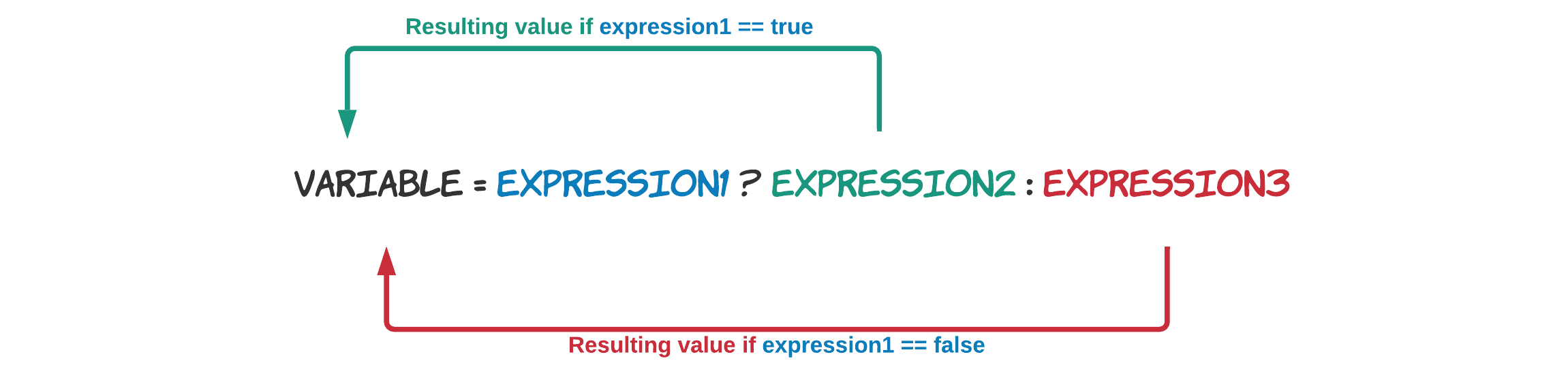

# The Conditional Operator

The conditional operator returns one of two values depending on the result of an expression. The returned value can then be used in another expression or assigned to a variable for later use.

Its syntax is as follows:

(expression1) ? expression2 : expression3Copied!

The parentheses around the first expression are optional but most programmers will place them as often the first expression is a conditional expression.

An example will greatly clarify things:

int someValue = -13; int absoluteValue = (someValue > 0) ? someValue : -someValue;Copied!

2

Basically the previous code snippet converts a signed integral value to its absolute value (value without a sign).

The conditional operator is the only operator in C++ that takes three operands. That's why it is also often called the ternary operator.

While it is possible to nest the ternary operator, it is strongly discouraged as it will lead to unreadable constructions.

# BitWise Operators

Bitwise operators work on bits and perform bit-by-bit operations.

# Boolean Operators

The next table shows an overview of the boolean operators supported by C++.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

& | Boolean AND operator |

| | Boolean OR operator |

~ | Boolean NOT operator |

^ | Boolean XOR operator |

Note that the NOT operator is the only boolean unary operator as it only takes a single argument. The other operators are all binary operators.

Study the example below. The results are shown in comments:

unsigned char a = 0b1010'1010; unsigned char b = 0b0000'1111; unsigned char x = a & b; // 0b0000'1010 unsigned char y = a | b; // 0b1010'1111 unsigned char z = a ^ b; // 0b1010'0101 unsigned char w = ~b; // 0b1111'0000Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

# Shift Operators

The shift operators bitwise shift the value off their left operand by the number of bits given as their right operand.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

<< | left shift |

>> | right shift |

Both operators take two operands. On the left side the value to shift and on the right side the number of places to shift.

Left shifting an integer a with an integer b (a << b) is equivalent to multiplying a with 2^b (2 raised to the power b) while right shifting an integer a with an integer b (a >> b) is equivalent to diving a with 2^b.

int x = 16; int shifted = (x << 2); cout << "Shifting " << x << " two bits to the left: " << shifted << endl;Copied!

2

3

4

Output

Shifting 16 two bits to the left: 64

Notice that the << symbols are both used for passing data to cout as for shifting bits in integral values. C++ is smart enough to detect the operation that needs to be performed based on the context of the code.

The left shift operator will shift in zero's on the LSB side. The right shift operator adds either 0s, if the left-side operand is an unsigned type, or extends the MSB (to preserve the sign) if its a signed type.

Care should be taken when the values of either operand might be negative because:

- For negative

a, the behavior ofa << bis undefined. - For negative

a, the value ofa >> bis implementation-defined (in most implementations, this performs arithmetic right shift, so that the result remains negative). - If the value of the right operand (

b) is negative, the behavior is undefined.

If the number is shifted more than the size of integer, the behavior is also undefined. For example, 1 << 33 is undefined if integers are stored using 32 bits.

# Assignment Operators

Next to the basic assignment operator =, C++ also supports a whole collection of compound assignment operators.

Programmers are very lazy creatures that are always looking for ways to make their life's easier. That is why the compound operators were invented. They are a way to write shorter mathematical operations on the same variable as the result should be stored in.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

= | Assign value from right operand to left operand. |

+= | Add left operand to right operand and assign result to left operand |

-= | Subtract left operand from right operand and assign result to left operand |

*= | Multiply left operand by right operand and assign result to left operand |

/= | Divide left operand by right operand and assign result to left operand |

%= | Divide left operand by right operand and assign remainder to left operand |

<<= | Left shift left operand by right operand and assign result to left operand |

>>= | Right shift left operand by right operand and assign result to left operand |

&= | Bitwise AND left operand with right operand and assign result to left operand |

|= | Bitwise OR left operand with right operand and assign result to left operand |

^= | Bitwise XOR left operand with right operand and assign result to left operand |

Note that there are no compound operators available for the logical operators.

int x = 5; x += 4; // Same as writing x = x + 4; x -= 4; // Same as writing x = x - 4; x *= 4; // Same as writing x = x * 4; x /= 4; // Same as writing x = x / 4; x %= 4; // Same as writing x = x % 4;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

# The sizeof Operator

sizeof is a compile-time operator (not run-time) that determines the size, in bytes, of a variable or data type. Basically it tells you how much memory is required to store a a value of the given datatype. It can be used to get the size of classes, structures, unions, arrays and any other user defined data type.

The syntax of using sizeof is as follows:

sizeof(datatype/variable)Copied!

cout << "Size of a char: " << sizeof(char) << " bytes." << endl; cout << "Size of a short: " << sizeof(short) << " bytes." << endl; cout << "Size of an integer: " << sizeof(int) << " bytes." << endl; cout << "Size of a long: " << sizeof(long) << " bytes." << endl; cout << "Size of a long long: " << sizeof(long long) << " bytes." << endl;Copied!

2

3

4

5

Output

Size of a char: 1 bytes. Size of a short: 2 bytes. Size of an integer: 4 bytes. Size of a long: 8 bytes. Size of a long long: 8 bytes.

Datatypes

Remember that the size of the datatypes can differ on your system as C++ does not enforce an exact size for each datatype.

# Number of Operands

Operators can also be categorized depending on the number of operands they take.

Unary Operators: Unary operators only require a single operand. The most common example is the minus-operators, which changes the sign of the value provided as the operand. For example:

-3.Binary Operators: Binary operators require two operands to perform their operation. The arithmetic operators are the most familiar examples of binary operators. For example:

health + 15, where the operator is+, andhealthand15are the operands.Ternary Operator: The C++ language has only a single ternary operator, namely the conditional operator

?:, often also called THE ternary operator. Ex. `(age > 18 ? "Adult" : "Non-Adult"). The result of this ternary operator can then be assigned to a variable or used somewhere else in code.

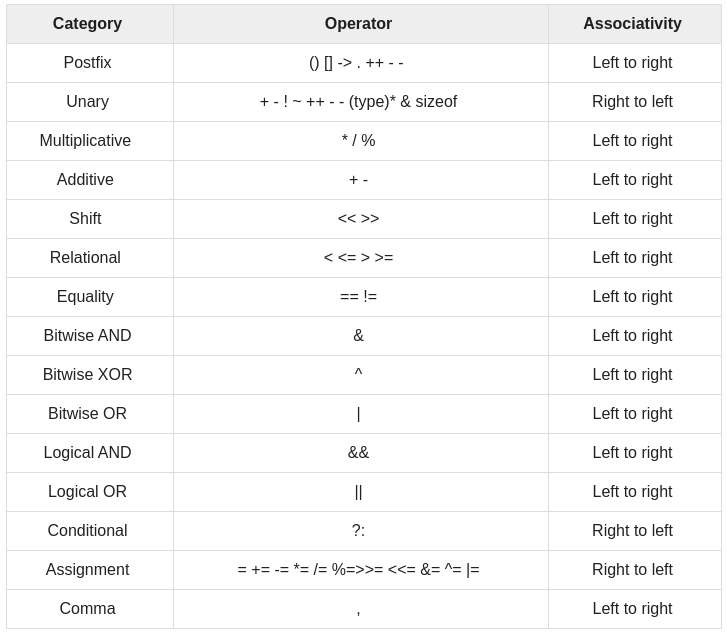

# List of C++ Operators

While not all operators are discussed in this chapter, here is a list of the most common C++ operators, their precedence and associativity. Operators with the highest precedence appear at the top of the table, those with the lowest appear at the bottom. Within an expression, higher precedence operators will be evaluated first.

By the end of this course all these operators should be clear to you.

# Exercises

Try to solve the exercises yourself. Don't go copy pasting other people's solutions.

Mark the exercises using a ✅ once they are finished.

# ❌ Squaring a number

How would you square the value in x and store it in squared? Use only the basic math operators.

int x = 12; int squared;Copied!

2

3

# ❌ 24 hours

Consider the following example, a code snippet from a student, programming a clock which can display the time in 24h format. The student however has a small problem where the hours sometimes become bigger than 23. Can you think of a single operator statement to limit the hours to a value between 0 and 23?

int hours = 25; // How can we limit hours here so it wraps around to 1?Copied!

2

3

# ❌ Incrementing an Expression

Knowing what you know now, could you answer the following question? Would it be possible to use the increment operator on an expression as demonstrated in the following code snippet?

int x = 12; int y = 34; int z = (x + y)++;Copied!

2

3

4

# ❌ Literals

Consider the code snippet below. What are the literals in this code?

int x = 12; int y = 5; int result = (x + y) * (x + y); cout << "The result is " << result << endl;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6