# Pointers

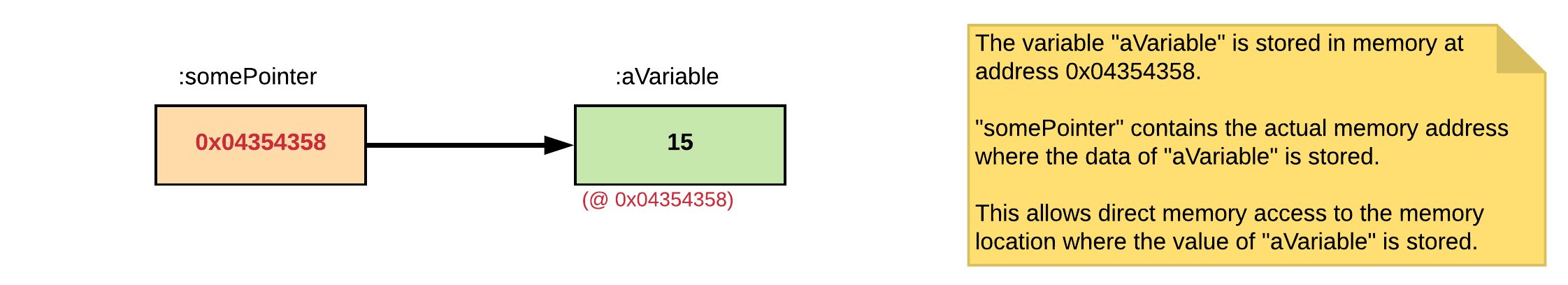

A pointer is a variable which holds the address to a location in memory. C++ gives you the power to manipulate data in the computer's memory directly via a pointer. C++ pointers may seem complex at first, but when used correctly they can be very powerfull. In certain areas they cannot be avoided, such as for example when handling dynamic memory allocation.

# Getting the Address of a Variable

As stated before, a variable is a symbolic name for a certain location inside your computer memory. This location is actually an address. Using the reference operator & one can determine the address of the variable. Consider the following example which will print the address of the variables x and y:

#include <iostream> int main() { int x = 15; int y = 0; std::cout << "x = " << x << " and has an address of " << &x << std::endl; std::cout << "y = " << y << " and has an address of " << &y << std::endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

which would output something similar to:

Output

x = 15 and has an address of 0x6afefc y = 0 and has an address of 0x6afef8

Logical, not physical addresses

Basically, any pointers in a program are logical (also called virtual) addresses, never physical (unless you are not running under an operating system - for example on a microcontroller). User space applications have no way of accessing the memory using physical addresses - that's one of the abstractions the OS gives each process. The MMU (Memory management unit) does the translation for every memory access, and it's up to the OS to set up the correct mapping for your process. To do all this in a way that goes completely unnoticed by processes, it has to create a layer of memory mappings that map the pointers that a process has to their actual physical location. But, certainly, the pointers that a program holds are indeed virtual addresses, the proof is simple: they don't change even as the process memory is relocated. Another indication of that is also the fact that if you try to access memory that isn't allocated to the current process, you get a "segmentation fault" or "access violation" error from the OS.

# Declaring a Pointer Variable

Like any variable or constant, you must declare a pointer before you can work with it. As C++ is a statically typed language, the type is required to declare a pointer - this is the type of the data that will live at the memory address the pointer points to. The general form of a pointer variable declaration is:

<type> * variable_name;Copied!

Basically this can be translated to variable_name is a pointer which can hold the address of a memory location containing a type. The type can be any valid C++ type, such as the primitive types, classes, structs, ...

Take a look at the following examples:

int * pointerToInt; // Pointer to an integer double * pointerToDouble; // Pointer to a double float * pointerToFloat; // Pointer to a float char * pointerToChar; // Pointer to character Student * pointerToStudent; // Pointer to an object of class Student std::string * pointerToString; // Pointer to an object of type std::stringCopied!

2

3

4

5

6

The actual data type of the value of all pointers themselves, whether integer, float, character, or otherwise, is the same, a long hexadecimal number that represents a memory address. The only difference between pointers of different data types is the data type of the variable or constant that the pointer actually points to.

# Initializing a Pointer

As with any other variable, a pointer needs to be initialized before it can be used. To accomplish this, one needs to assign the address of a variable to the pointer. As shown before, the address of a variable can be retrieved by applying the address-of operator & to it. The resulting address can then be assigned to a pointer of the same type as the variable.

// A pointer to a variable of type int int x = 15; int * pointerToX = &x; // A pointer to a variable of type double double z = 25.3; double * pointerToZ = &z; // A pointer to an object of type std::string std::string greeting = "Hello there"; std::string * pointerToGreeting = &greeting;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# Using Pointers

Pointers are mainly used to directly access the memory they are pointing to. So in other words, one needs to be able to access the actual data and not the address inside the pointer. This can be achieved by dereferencing the pointer using the dereference operator *. Once the pointer is dereferenced, it can be threated as a normal variable.

An example where a pointer to an integer variable is used to change the actual value of the integer variable:

#include <iostream> int main() { int x = 15; int * pointerToX = &x; // Make pointer point to memory location of x // Dereferencing the pointer to access the actual data (*pointerToX) = 22; std::cout << "x = " << x; std::cout << " or via pointer = " << (*pointerToX) << std::endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Output

x = 22 or via pointer = 22

While not strictly necessary to add parentheses around the dereferenced pointers (as the dereference operator has a high precedence), it often makes the code more clear.

This is also the reason why a pointer needs a dataype. Because the compiler needs to know how to derefence the pointer to access the actual data in memory. It needs to know the type and size of the memory block the pointer is pointing to.

# Pointers and Arrays

Not correct

This sections contains some inaccurate information. In fact arrays are not constant pointers but it is said that in certain situation the array decays to a pointer. For example when passing the array to a function/method. Decaying means that the size information is lost of the array.

It's said that arrays "decay" into pointers. A C++ array declared as int numbers [5] cannot be re-pointed, i.e. you can't say numbers = 0x5a5aff23. More importantly the term decay signifies loss of type and dimension; numbers decay into int* by losing the dimension information (count 5) and the type is not int [5] any more. Look here for cases where the decay doesn't happen. If you're passing an array by value, what you're really doing is copying a pointer - a pointer to the array's first element is copied to the parameter (whose type should also be a pointer the array element's type). This works due to array's decaying nature; once decayed, sizeof no longer gives the complete array's size, because it essentially becomes a pointer. This is why it's preferred (among other reasons) to pass by reference or pointer.

void by_value(const T* array) // const T array[] means the same void by_pointer(const T (*array)[U]) void by_reference(const T (&array)[U])Copied!

2

3

The last two will give proper sizeof info, while the first one won't since the array argument has decayed to be assigned to the parameter. The big problem here is that the constant U should be known at compile-time.

Pointers and arrays are strongly related. In fact, an array variable is nothing more than a constant pointer pointing at the first element of the array. Actually a pointer can be dereferenced using the indexing operator [] used on an array variable as shown in the example below:

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main() { int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; // Array is a const pointer meaning we can ask for the address: cout << "Address of first element:\t" << numbers << endl; // Or derefence the array and access the first element cout << "First element via derefence:\t" << *numbers << endl; // We can assign array to pointer int * pNumber = numbers; cout << "Address stored in pNumber:\t" << pNumber << endl; cout << "Value pointed at by pNumber:\t" << *pNumber << endl; // Or using the indexing operator in the pointer: cout << "First element via []:\t\t" << pNumber[0] << endl; cout << "Second element via []:\t\t" << pNumber[1] << endl; // We can also request address of element in array // and treat pointer as array again: int * fromSecond = &(numbers[1]); cout << "First element of fromSecond:\t" << fromSecond[0] << endl; cout << "Second element of fromSecond:\t" << fromSecond[1] << endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Output

Address of first element: 0x7ffeb1f0b51c First element via derefence: 123 Address stored in pNumber: 0x7ffeb1f0b51c Value pointed at by pNumber: 123 First element via []: 123 Second element via []: 21 First element of fromSecond: 21 Second element of fromSecond: 33

Also note that one does not need to request the address of the array to initialize the pointer. This because the array variable is already a pointer. Of course if you do wish to use the address-of operator you can use the following construct:

int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; int * pNumbers = &(numbers[0]);Copied!

2

This would allow you to create a pointer to an element somewhere inside the boundaries of the array. For example for the second element:

int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; int * fromSecond = &(numbers[1]);Copied!

2

Since an array variable is actually a pointer, it is perfectly valid to dereference it using the dereference operator *.

int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; (*numbers) = 15; // Would change the first element to a value of 15Copied!

2

3

However do keep in mind that an array variable is a constant pointer. This means that the array variable itself cannot be made to point to something else than the first element of the actual array in memory.

int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; // Invalid !!!!!! numbers = &(numbers[2]);Copied!

2

3

4

Since an array is a constant pointer, it is also possible to use the indexing operator [] on a pointer to use a pointer as an array. The example below shows a small example where a pointer is indexed:

int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; int * pNumbers = numbers; // Indexing of normal pointer as with an array cout << "First element via []:\t\t" << pNumber[0] << endl;Copied!

2

3

4

5

Note that the indexing operator already dereferences the actual address.

# Pointer Arithmetic

Since pointers hold addresses, it is perfectly legal to perform some arithmetic operations on the actual address value held by the pointer. There are four arithmetic operators that can be performed on pointers:

- Increment:

++ - Decrement:

-- - Addition:

+ - Subtraction:

-

To understand pointer arithmetic one needs to keep in mind that the size of the datatype to which the pointer refers to, is also put into account. This means that if you have a pointer that points to integer at memory address 5000 on a 32-bit computer and you increment the pointer you will end up at address 5001, assuming that the integer is represented using 32 bits. However, if you are working on an 8-bit computer, assuming that the integer is represented using 32 bits, incrementing the pointer will result in ending up at address 5004.

This can actually be used in combination with a pointer to an array. Take a close look at the example below where a pointer is incremented to index all the array elements:

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main() { int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; // Pointer pointing to first element of array int * pNumbers = numbers; for (unsigned int i = 0; i < sizeof(numbers)/sizeof(int); i++) { std::cout << "numbers[" << i << "] @ " << pNumbers << " = " << *(pNumbers) << std::endl; // Increment address (jumps to next element) // takes size of int into account pNumbers++; } return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Output

numbers[0] @ 0x7fffe60b064c = 123 numbers[1] @ 0x7fffe60b0650 = 21 numbers[2] @ 0x7fffe60b0654 = 33

Since an array is a constant pointer, it is also possible to use the indexing operator [] on a pointer to use a pointer as an array. The example below shows both the usage of using the indexing opator [] on a pointer, as applying some pointer arithmetics.

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main() { const int SIZE_OF_NUMBERS = 5; int numbers[SIZE_OF_NUMBERS]; // Array is nothing but constant pointer so int * pNumbers = numbers; int * pNumbersIncrement = numbers; cout << "Address of numbers: " << numbers << endl; cout << "Or via pointer: " << pNumbers << endl << endl; for (unsigned int i = 0; i < SIZE_OF_NUMBERS; i++) { // Incrementing a pointer (point to next memory value) cout << "@" << pNumbersIncrement << ": " << *(pNumbersIncrement) << endl; pNumbersIncrement++; // One can also use indexing operator on pointer cout << "@" << &(pNumbers[i]) << ": " << pNumbers[i] << endl; // Simple addition cout << "@" << (pNumbers+i) << ": " << *(pNumbers+i) << endl << endl; } return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

which would result in a similar output:

Output

Address of numbers: 0x61fef0 Or via pointer: 0x61fef0 @0x61fef0: 4201424 @0x61fef0: 4201424 @0x61fef0: 4201424 @0x61fef4: 6422240 @0x61fef4: 6422240 @0x61fef4: 6422240 @0x61fef8: 6422296 @0x61fef8: 6422296 @0x61fef8: 6422296 @0x61fefc: 6422476 @0x61fefc: 6422476 @0x61fefc: 6422476 @0x61ff00: 1996867696 @0x61ff00: 1996867696 @0x61ff00: 1996867696

# Passing Pointers as Parameters

C++ allows you to pass a pointer as a parameter to a function/method. To do so, simply declare the function parameter as a pointer type.

Passing data to functions via pointers is often applied in the following situations:

- to allow the function to alter the actual value of the passed arguments

- to be able to return more than one value from a function (this is often used in C, less required in C++ as one can use data objects in this case)

- performance wise it is often done to pass larger and more complex objects (less memory usage and faster than copying complex objects)

- to pass an array to a function

# Passing Basic Data Types

Remember the swap() function from the "Introduction to C++" chapter. To get this to work one can actually use pointers to integers:

#include <iostream> using namespace std; void swap(int * x, int * y) { int temp = *x; *x = *y; *y = temp; } int main() { int a = 10; int b = 136; cout << "Before call to swap:" << endl; cout << "a: " << a << endl; cout << "b: " << b << endl; swap(&a, &b); cout << "\nAfter call to swap:" << endl; cout << "a: " << a << endl; cout << "b: " << b << endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

While the parameters are still passed by value, this time the addresses to the actual memory are copied. However via that same address one has access to the original data.

Output

Before call to swap: a: 10 b: 136 After call to swap: a: 136 b: 10

# Passing Arrays

Faulty Info

Again this section contains some inaccurate information

Since arrays are nothing more than constant pointers to the first element in the array, passing arrays is quite straight-forward. One thing to keep in mind is that there is no way to determine the number of elements inside the array when leaving the scope of the where the array was declared. On other words, you will always need to pass the length of the array to the function/method.

#include <iostream> using namespace std; void print_numbers(int values[], unsigned int length) { // We need length here because size(values) would return the // sizeof a pointer here (even compiler warns about this) // Try it: cout << "Sizeof(values) in print_numbers: " << sizeof(values) << " bytes" << endl << endl; cout << "| "; for (unsigned int i = 0; i < length; i++) { cout << values[i] << " | "; } cout << endl; } int main() { int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; // We can only use the sizeof() trick here because // the array was declared in this scope cout << "Sizeof(values) in main: " << sizeof(numbers) << " bytes" << endl; cout << "Sizeof(int) in main: " << sizeof(int) << " bytes" << endl; // So we determine length by using: print_numbers(numbers, sizeof(numbers)/sizeof(int)); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Output

Sizeof(values) in main: 12 bytes Sizeof(int) in main: 4 bytes Sizeof(values) in print_numbers: 8 bytes | 123 | 21 | 33 |

Since arrays are constant pointers it is also perfectly legal to pass an array to a pointer argument:

#include <iostream> using namespace std; void reverse_elements(int * const values, unsigned int length) { // Notice the pointer syntax of values. By declaring the pointer // to be const we can also protect it from being re-assigned. for (unsigned int i = 0; i < length / 2; i++) { int temp = values[i]; values[i] = values[length-1-i]; values[length-1-i] = temp; } } void print_numbers(int values[], unsigned int length) { cout << "| "; for (unsigned int i = 0; i < length; i++) { cout << values[i] << " | "; } cout << endl; } int main() { int numbers[] = { 123, 21, 33 }; // So we determine length by using: print_numbers(numbers, sizeof(numbers)/sizeof(int)); // Reversing the elements of the array reverse_elements(numbers, sizeof(numbers)/sizeof(int)); print_numbers(numbers, sizeof(numbers)/sizeof(int)); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Output

| 123 | 21 | 33 | | 33 | 21 | 123 |

While not mandatory we can also declare the pointer to be const. Meaning it cannot be assigned to point to another memory location. Not the same as const int * values which would mean that we could not change the values of the array.

# Passing Objects

Consider a small class Student:

// student.h #pragma once class Student { public: Student(std::string name); std::string get_name(void); private: std::string name; };Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// student.cpp #include "student.h" Student::Student(std::string name) { this->name = name; } std::string Student::get_name(void) { return name; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Assume a small function in main that prints out the name of a student to the terminal. To pass a pointer to a student to the function one just needs to declare a pointer as parameter:

void print_student(Student * student) { // ... }Copied!

2

3

To access member attributes or methods of an object via a pointer, one first needs to dereference the pointer before using the member-operator . on it. As with any pointer, dereferencing is done using the dereference operator *.

#include <iostream> #include "student.h" using namespace std; void print_student(Student * student) { cout << "Our student is named " << (*student).get_name() << endl; } using namespace std; int main() { Student mark("Mark Dekker"); print_student(&mark); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Output

Our student is named Mark Dekker

Note how the dereference operation is enclosed in round brackets.

Since this is used so many times in C++, the language included a shorter and more clean operator that allows the programmer to dereference a pointer to an object and call a member of it, namely the arrow operator ->. So the example above can be rewritten as:

#include <iostream> #include "student.h" using namespace std; void print_student(Student * student) { cout << "Our student is named " << student->get_name() << endl; } using namespace std; int main() { Student mark("Mark Dekker"); print_student(&mark); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

This is the same notation as used inside a method when accessing the this reference of the instantiated object.

# So Why Pointers?

TODO - Explain more in detail

- Arrays are pointers

- Allow functions/methods to manipulate incoming data

- Dynamic Memory will require pointer usage (later)

- Performance and Memory Usage (instead of copying large complex data)

- Sharing data/memory/objects between objects

- File handling (read, write, ...)

this= pointer to current instance- To return multiple values

- Implementing data structures (linked list, trees, maps, ...)

- Pointers to functions/methods, allowing callbacks and dynamic behavior

- System level programming where memory addresses are a necessity