# Dynamic Memory Allocation

Basically when executing an application on any machine - be it a server, a desktop or an embedded system - the application requires at least a processing unit (CPU) and memory.

C++ will store data in different places based on how and where in code they were created. The programmer is given the choice based on efficiency and necessity. For maximum runtime speed, the storage and lifetime can be determined by the programmer while the program is being written.

# Memory Segments

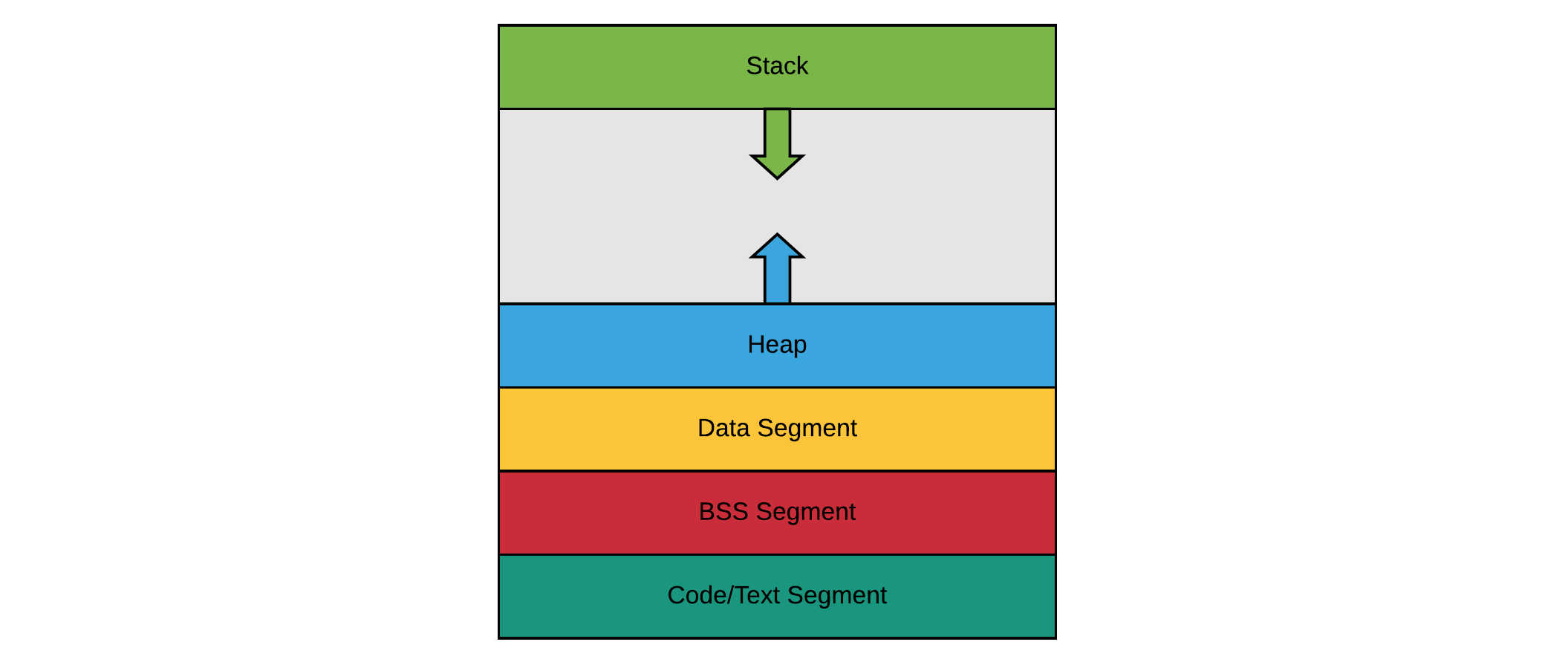

The memory that is a assigned to an application when it is being run is typically divided in different regions called memory segments:

- The code segment, also called the text segment, is where the compiled binary resides in memory. This is typically a read-only memory segment.

- The bss segment, hosts zero-initialized global and static variables.

- The data segment, hosts initialized global and static variables.

- The heap is used to provide memory at runtime when the application requests dynamically allocated memory.

- The stack, tracks function arguments, local variables and other function-related information.

For the moment the two most important regions for this course are the stack and heap segments.

# The Stack

The stack, often called the call stack, is a memory region implemented as a stack structure (hence the name). It has quitte a big role to play when executing an application on a system. It keeps track of

- all functions that have been called but have not yet terminated since the execution start of the application to the current point of execution.

- the return address to where to jump after a function has terminated

- all function parameters that are required upon calling the function

- all local variables of the functions

# Calling a Function

Let us take a closer look at the inner workings of the stack when the program encounters a function call.

- First a stack frame is constructed and placed on the stack by the means of a push action. A stack frame contains the return address to which the CPU must jump after the function has terminated, the function arguments, memory for the local variables declared inside the function and last but not least some CPU register values that need to be restored after the function finishes.

- Once the stack frame is pushed, the CPU jumps to the first instruction in the function to be executed by the processor.

- The CPU continues executing instructions until the function is finished or control jumps to another function in which case the whole process repeats for the new function call.

At a certain point in time the function should terminate, which again consists of a number of steps.

- First register values are restored to the state before the function was called.

- Next the stack frame is removed from the stack (it is popped from the stack). This frees up all the previously allocated variables in the function (function parameters and local variables).

- Next the return value is handled. Depending on the computer's architecture, the function's return value is placed inside a processor register or placed on the stack. If the value of the function isn’t assigned to anything, no assignment takes place, and the value is lost.

- Last the return address of the next instruction to execute is popped off the stack, and the CPU resumes execution at that instruction.

# Variables on the Stack

All the variables, arguments and objects shown in the next code sample are placed on the stack.

#include <vector> #include <string> double foo(int x) { std::vector<std::string> listOfStrings; int numbers[100]; double sum = 0; // .... return sum; } int main(void) { int value = 55; // Calling a function uses the stack double result = foo(value); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

The stack is an area in memory that is used directly by the processor to store data during program execution. Variables on the stack are also called automatic or scoped variables. This because the memory is automatically freed once the variables go out of scope.

The stack memory is a fixed size memory region that is allocated before the program is used. Allocating static storage is much more speed-optimized, which can be important in certain situations.

It does however require you to know the exact quantity, lifetime and type of the objects when you are writing the program. Besides that the stack is also limited in size. This means that you can overflow the stack, especially on smaller embedded systems this can be a limiting factor.

# Stack Overflow

The stack and heap sizes are determined by the operating system on which the application is being run. The stack and heap memory are not included in the binary stored on disk. When a process is loaded in memory then the stack and heap segments are allocated for that process.

A stack overflow occurs if the call stack pointer exceeds the stack bound. In other words, the application is using more stack memory than there was allocated. When a program attempts to use more space than is available on the call stack (that is, when it attempts to access memory beyond the call stack's bounds, which is essentially a buffer overflow), the stack is said to overflow, typically resulting in a program crash.

On Windows, the default stack size is 1MB. On some unix machines, it can be as large as 8MB.

Stack overflow is generally the result of allocating too many variables on the stack, and/or making too many nested function calls (where function A calls function B calls function C calls function D etc) On modern operating systems, overflowing the stack will generally cause your OS to issue an access violation and terminate the program.

The following program tries to reserve 10 million doubles on the stack. Of course this results in a stack overflow.

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main(void) { // This will create a stack overflow double loadsOfNumbers[10000000]; cout << "You won't see this as the app will crash" << endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

The next application has a recursive function that calls itself. It keeps doing this until the application crashes. While the number of iterations is quite high when running this application, you should try to add some local variables to the function. This will greatly decrease the number of iterations.

#include <iostream> #include <vector> #include <string> using namespace std; int count(int iNesting) { iNesting++; cout << "Current iteration: " << iNesting << endl; return count(iNesting); } int main(void) { // Call some recursive function that never stops. // This will generate a stack overflow count(0); return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Output

... Current iteration: 261794 Current iteration: 261795 Current iteration: 261796 Current iteration: 261797 Current iteration: 261798 [1] 9582 segmentation fault (core dumped) ./stack

While this is not a realistic example, it does show that their is a limit to how deep functions can be nested. This limit only decreases as functions take more stack space. This can become problematic quite fast on embedded systems with limited memory.

# The Heap

The heap segment - also knows as the "free store" - is a memory region used for allocating dynamic memory at runtime. Dynamic memory allocation is a way for application to request memory from the operating system at runtime.

Dynamic memory is requested in C++ using the new operator or the malloc function. Both these operations return a pointer to the requested memory block. If the system runs out of memory (especially important on smaller embedded systems) this operation can fail. In that case an exception is thrown.

The process of allocating memory from the heap is also slower as it must pass via the operating system. On top of that dereferencing pointers is also a slower process that accessing memory via variables on the stack.

Important to know is that dynamically allocated memory is not freed automatically, as is the case with local variables on the stack. It is the programmers responsibility to free the memory when it is no langer needed. Failing to do so can create memory leaks and can eventually cause the program to crash.

Looking back at heap memory it seems that it only has disadvantages. However the biggest advantage is the fact that the programmer does not need to know how much memory is required at compile-time. This memory does not come from the program’s limited stack memory -- instead, it is allocated from a much larger pool of memory managed by the operating system called the heap. On modern machines, the heap can be gigabytes in size.

If you don't know how many objects you will need until runtime, what their lifetime is or what their exact type is, you will need to allocate your objects on the heap.

# When to use the heap

If we have to declare the size of everything at compile time, the best we can do is try to make a guess the maximum size of variables we’ll need and hope that’s enough:

char email[50]; // Hopefully the email is shorter than 50 characters Record record[500]; // Let us hope there are less than 500 records! Polygon rendering[30000]; // 3D rendering can only handle 30k polygonsCopied!

2

3

There are some reasons why this is not the best solution:

It leads to wasted memory if the variables aren’t actually used. For example, consider the rendering array above: if a rendering only uses 10k polygons, we have 20k Polygons worth of memory not being used.

Using the stack can lead to artificial limitations and/or array overflows. What happens when the user tries to read in 600 records from disk, but we’ve only allocated memory for a maximum of 500 records? Either we have to give the user an error, only read the 500 records, or (in the worst case where we don’t handle this case at all) overflow the record array and watch something bad happen.

The amount of stack memory for a program is generally quite small. If the data structure is complex or big, it is also better to create it on the heap. If you exceed the stack size limit, a stack overflow will occur, and the operating system will close down the application. The size of the heap is set on application startup, but can grow as space is needed (the allocator requests more memory from the operating system), so as long as the operating system is willing to provide memory, the heap can grow.

On top of this, it is also inefficient to pass large and complex objects declared on the stack to functions. They will be passed by value and therefore be copied into a new variable on the stack, taking space everytime they are passed to a function.

// TODO: Example on passing complex objects via stack // Can valgrind profile this?Copied!

2

# Stack versus Heap

Declaring variables on the stack has both advantages and disadvantages:

- ✔️ Allocating stack memory is faster than allocating heap memory

- ✔️ Variables are automatically deallocated when the function terminates. It is said that the variables go out of scope.

- ✔️ Variables allocated on the stack have a known data type at compile time. This means that the allocated memory can be accessed directly through the variables.

- ❌ The stack is relatively small, which means it's not a good idea to create large local variables on the stack (complex objects, large arrays and such). Also nesting function calls too deep has a serious impact on stack usage.

Also requesting memory from the heap has some advantages and disadvatages:

- ❌ Allocating memory on the heap is slow compared to on the stack

- ❌ Allocated heap memory is not automatically deallocated. This can create memory leaks while the application is running. Most operating systems these days will free the memory after the application is terminated. However some applications such as background services may not terminate for many months/years.

- ❌ Dynamically allocated memory is handled via pointers. Dereferencing pointers is a relative slower process compared to using variables on the stack.

- ✔️ The heap is a big memory pool that allows us to allocate large blocks of memory for more complex objects, large arrays and such.

# Dynamically Allocating Memory in C++

Allocating memory on the heap in C++ is accomplished using the new operator which returns a pointer to the newly allocated block of memory.

As mentioned before, it is critical that the memory be freed when it is not needed anymore. This can be achieved using the delete operator, called on the pointer. Every new should have a matching delete in your code. Failing to do so creates memory leaks in your application which can lead to program crashes.

Memory Leak

A memory leak is created when memory is allocated but not released causing an application to consume memory reducing the available memory for other applications and eventually causing the system to page virtual memory to the hard drive slowing the application or crashing the application when the computer memory resource limits are reached. The system may stop working as these limits are approached.

# Allocating Primitive Data Types

Take a basic example that request an integer to be allocated on the heap. It uses the integer to store a value and output it to the standard output. The memory is freed after usage.

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main(void) { // Allocate integer on the heap int * number = new int; // Assign value to number *number = 42; cout << "Number is now " << *number << endl; // Delete the memory delete number; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

delete

The delete operator does not actually delete anything. It simply returns the memory being pointed to back to the operating system. The operating system is then free to reassign that memory to another application (or to this application again later). Although it looks like a variable is being deleted, this is not the case. The pointer variable itself still has the same scope as before, and can be assigned a new value just like any other variable. In other words the pointer variable itself actually resides on the stack, while the memory it pointed too was allocated on the heap.

# Creating and Destroying Objects on the Heap

Another important difference between dynamic and automatic allocation is the fact that the compiler can automatically destroy objects that were created on the stack. This because the exact lifetime of those objects is known. This is not the case for objects that are created on the heap; the compiler has no knowledge of their lifetime. In C++ this is the responsibility of the programmer. If done incorrectly or not at all, the application will contain memory leaks.

To create objects on the heap, memory must be requested by using the new keyword as shown in the next code snippet:

Foo * myObject = new Foo();Copied!

Note how the actual variable is now a pointer to an object of type Foo. This is necessary because the new operator returns a pointer to a memory region, on the heap, occupying a Foo object.

As mentioned before, the compiler cannot automatically destroy the memory that is reserved on the heap as it does not know the lifetime of the objects. This is a responsibility of the programmer. This can be accomplished by freeing the memory once the application has no more use for it. For this the delete operator can be used.

Foo * myObject = new Foo(); // .... use the object // Free the memory delete myObject;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

A new must always be accompanied by a delete somewhere in your application. If not, your application creates memory leaks.

Never access a pointer to an object after deleting it. The resulting behavior is undefined, and if you are lucky the program just crashes.

# Destructors

Now what if an object of a class that you created needs internal dynamic memory. In many cases this memory only needs to be freed when the object is actually destroyed.

This is where destructors come in to play. They are similar to constructors but instead of being responsible for the creation of an object of the class, they are responsible for the destruction of it.

A destructor has the following properties:

- it is a member method of the class

- it had the exact same name as the class, prefixed with a

~ - it does not take any arguments; this also means it cannot be overloaded

- it has no return type, not even void

For example:

Foo::~Foo(void) { // Do destruction stuff such as freeing memory }Copied!

2

3

# Creating and Destroying arrays on the heap

To dynamically allocate an array one needs to use the new[] operator. To free the memory, the delete[] keyword is required.

Let us take a look at a basic example.

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main(void) { // Allocate array of integers on the heap int * numbers = new int[5]; // Assign value to first number numbers[0] = 42; cout << "First number is now " << numbers[0] << endl; // Delete the memory delete[] numbers; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# An RGB Led Class

Let's take a look at a more complete example where all these things come together.

The following implementation models an RgbLed class that contains (is composed of) a Color object, modeling the three color components that make up a colored led.

Color class

The implementation of the Color class can be found in 04 - Basics of Classes.

#pragma once #include "color.h" namespace Hardware { class RgbLed { // Constructors public: RgbLed(void); RgbLed(Visual::Color color); // Setters public: void set_color(Visual::Color color); // Getters public: Visual::Color get_color(void); // Attributes private: Visual::Color color; }; };Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Note that the RgbLed class has two constructors (constructor overloading):

- a default constructor (that takes no arguments)

- a second constructor that allows us to initialize the led to a certain color

The implementation that belongs to the previous header file is shown below.

#include "rgb_led.h" using namespace Visual; namespace Hardware { RgbLed::RgbLed(void) : RgbLed(Color(255, 0, 0)) { } RgbLed::RgbLed(Color color) { set_color(color); } void RgbLed::set_color(Color color) { this->color = color; } Color RgbLed::get_color(void) { return color; } };Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

While most of the code is self-explanatory, the default constructor does need some explanation.

RgbLed::RgbLed(void) : RgbLed(Color(255, 0, 0)) { }Copied!

2

3

The part after the colon : is called the constructor-initialization list an is executed before the body of the constructor. Here it allows us to call another constructor of the same class before executing the code of the current constructor. This allows us to keep the code as DRY as possible.

In other words, the default constructor here first calls the other constructor with all color components set to zero except the red one (remember that everything needs to be initialized) before it executes its own code (nothing in this case).

Let's take a look at a usage example where we create an object on the stack.

#include <iostream> #include "rgb_led.h" using namespace std; int main() { Hardware::RgbLed aliveLed; cout << "Red = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_red() << endl; cout << "Green = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_green() << endl; cout << "Blue = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_blue() << endl; cout << "Setting the color of the led to yellow:" << endl; aliveLed.set_color(Visual::Color(88, 88, 0)); cout << "Red = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_red() << endl; cout << "Green = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_green() << endl; cout << "Blue = " << aliveLed.get_color().get_blue() << endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

# An RGB Led Bar Class

A led bar is a bar with a certain number of leds. A typical led bar consists of eight leds. But what if we requested the number of LEDs from the user. In that case we do not know how many LEDs we initially need to provide. One could say, reserve enough, but what is enough? 255? If the user then only wanted 4 LEDs, it would be extremely inefficient.

So let's model an RGB led bar that can dynamically allocate the number of LEDs that is requested by the user at runtime.

#pragma once #include "rgb_led.h" #include <string> namespace Hardware { class RgbLedBar { // Constructors public: RgbLedBar(void); RgbLedBar(unsigned int numberOfLeds); // Destructors // - Required for freeing dynamically allocated memory public: ~RgbLedBar(void); // Getters public: RgbLed * get_led(unsigned int index); unsigned int get_length(void); // Other public: std::string to_string(void); // Attributes private: static const unsigned int DEFAULT_SIZE = 8; unsigned int numberOfLeds; RgbLed * leds; }; };Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

The actual led objects will be stored in an array leds which is declared as a pointer in the RgbLedBar class and not as an actual array using the [] notation. This because if we were to declare it as an array, we would need to supply the size and we also would not be able to assign it a new memory block afterwards (remember that an array is constant pointer). The actual memory for this array will be allocated dynamically at runtime in the constructor.

The number of LED's for the default constructor is not implemented as a magic number. A constant DEFAULT_SIZE under the form of a static class variable is added. This is more clear, more DRY and will allow us to easily change it if ever required.

Since objects of this class will be allocating dynamic memory (the array of leds), a destructor ~RgbLedBar() needs to be provided to free the memory after an object of this class is destroyed or goes out of scope.

#include "rgb_led_bar.h" namespace Hardware { RgbLedBar::RgbLedBar(void) : RgbLedBar(DEFAULT_SIZE) { } RgbLedBar::RgbLedBar(unsigned int numberOfLeds) { this->numberOfLeds = numberOfLeds; // Dynamically allocate memory for the array of leds leds = new RgbLed[this->numberOfLeds]; } RgbLedBar::~RgbLedBar(void) { delete[] leds; leds = nullptr; } RgbLed * RgbLedBar::get_led(unsigned int index) { if (index >= numberOfLeds) { return nullptr; } return &leds[index]; } unsigned int RgbLedBar::get_length(void) { return numberOfLeds; } std::string RgbLedBar::to_string(void) { std::string output = "RGB Led Bar: "; for (unsigned int i = 0; i < numberOfLeds; i++) { output += leds[i].to_string(); if (i < numberOfLeds-1) { output += " <=> "; } } return output; } };Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Something new here. The destructor needs to use the delete[] operator since leds is an array of objects and not a single object.

The get_led() method returns a pointer to an RgbLed object of the LED bar. Some mechanism should prevent that memory outside the array is accessed. Here a simple if-construct prevents this. Another option would of been to to throw an Exception. However this is course material for later.

Do note that it is mandatory for the get_led() method to return a pointer in every case, so also when index goes outside of bound. However we have no actual valid pointer to return here. For this we can make use of a special C++ keyword nullptr which is what is called a null-pointer. It actually points to nothing and is often used in cases where no valid pointer can be returned. Trying to use this null-pointer as it were a valid pointer does result in an application crash.

Why does `get_led()` return a pointer?

The method get_led() returns a pointer to the original object because we want the user of our class to be able to change the color of the leds. If we were to return the object itself, a copy would be returned (this is because functions and methods return by-value). Changing the color of this copy would not effect the origal led.

The next code snippet shows a usage example where the number of leds is requested from the user.

#include <iostream> #include "rgb_led_bar.h" using namespace std; int main() { cout << "Welcome to LED Bar Demo ..." << endl; unsigned int numberOfLeds = 0; cout << "How many leds would you like to add to the ledbar? "; cin >> numberOfLeds; cout << endl << "Creating a ledbar with " << numberOfLeds << " leds" << endl; Hardware::RgbLedBar bar(numberOfLeds); cout << bar.to_string() << endl; cout << endl << "Let us set some random colors:" << endl; srand(time(0)); for (unsigned int i = 0; i < bar.get_length(); i++) { bar.get_led(i)->set_color( Visual::Color(rand()%255, rand()%255, rand()%255) ); } cout << bar.to_string() << endl; return 0; }Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Output

Welcome to LED Bar Demo ... How many leds would you like to add to the ledbar? 5 Creating a ledbar with 5 leds RGB Led Bar: [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] Let us set some random colors: RGB Led Bar: [74, 117, 143] <=> [99, 30, 182] <=> [168, 100, 228] <=> [253, 179, 253] <=> [148, 162, 84]

Note that when the main function terminates (closing curly brace is reached), the bar object goes out of scope and the destructor is automatically called (as the RgbLedBar object itself was actually created on the stack).

# Detecting Memory Leaks using Valgrind

A good tool to check for memory leaks and many other bugs is valgrind. While this is a pure Linux tool, it can be used on the Windows Subsystem for Linux.

Just start valgrind and point it to your binary by executing the command as follows: valgrind -s <binary>.

Output

==15053== Memcheck, a memory error detector ==15053== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al. ==15053== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info ==15053== Command: ./bin/ledbar ==15053== Welcome to LED Bar Demo ... How many leds would you like to add to the ledbar? 5 Creating a ledbar with 5 leds RGB Led Bar: [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] <=> [255, 0, 0] Let us set some random colors: RGB Led Bar: [199, 159, 128] <=> [144, 124, 160] <=> [215, 72, 61] <=> [207, 153, 122] <=> [0, 123, 92] ==15053== ==15053== HEAP SUMMARY: ==15053== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks ==15053== total heap usage: 10 allocs, 10 frees, 75,238 bytes allocated ==15053== ==15053== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible ==15053== ==15053== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

::: hint Code https://github.com/BioBoost/course-object-oriented-programming-with-cpp/tree/master/docs/08-dynamic-memory-allocation/code/led-bar-demo (opens new window) :::

# Summary

Stack:

- Stored in computer RAM just like the heap.

- Variables created on the stack will go out of scope and automatically deallocated.

- Much faster to allocate in comparison to objects on the heap.

- Implemented with an actual stack data structure.

- Stores local data, return addresses, used for parameter passing

- Can have a stack overflow when too much of the stack is used. (mostly from infinite (or too much) recursion, very large allocations)

- Data created on the stack can be used without pointers.

- You would use the stack if you know exactly how much data you need to allocate before compile time and it is not too big.

- Usually has a maximum size already determined when your program starts

Heap:

- Stored in computer RAM just like the stack.

- In C++, variables on the heap must be destroyed manually and never fall out of scope. The data is freed with delete or delete[]

- Slower to allocate in comparison to variables on the stack.

- Used on demand to allocate a block of data for use by the program.

- Can have fragmentation when there are a lot of allocations and deallocations

- In C++, data created on the heap will be pointed to by pointers and allocated with new.

- Can have allocation failures if too big of a buffer is requested to be allocated.

- You would use the heap if you don't know exactly how much data you will need at run time or if you need to allocate a lot of data.

- Responsible for memory leaks

int foo() { // Nothing allocated yet // (excluding the pointer itself, // which is allocated on the stack). char *pBuffer; bool b = true; // Allocated on the stack. if(b) { // Create 500 chars on the stack char buffer[500]; // Create 500 chars on the heap pBuffer = new char[500]; } // buffer is deallocated here, pBuffer is not } // oops - memory leak, should have called delete[] pBuffer;Copied!

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

← Pointers Exceptions →